The war at the tip of the chronicle

Many of the most recent moments of the History of Manking reach us through the reports of journalists. It’s those moments that nobody wants to happen but that journalists love to report. The big war conflicts of the 20th Century are registered in some of the best journalism chronicles signed by the authors that stand out.

BEING A WAR CHRONICLER

Newspaper sent their first correspondents to the violence focus and, along with war reports, came the war chronicles. But was differentiated a war reporter from a war chronicler?

Many types, both genres were hand in hand. However, whilst the chronicle registers more opinionative aspects, the report searches more for the facts. In a true approximation of journalism to literature, the chronicle ends up for distinguishing itself with its own style. Proof of that is the appearance of the literary journalism.

JOHN SACK

This new genre was personified in the writing of many journalists. John Sack was one of them. By creating a creative narrative to report the facts, he produced the most moving stories of the war efforts.

His personal style of reporting the most cruel and violent war events consolidated with his long and lasting collaboration with the Esquiremagazine. Sack became a true expert in war journalism, even covering, in first hand, each USA war in the last 60 years.

Since the Korean War, to Vietnam’s, to the annexation of Kuwait by Iraque, and the Balkan war, John Sack would also accompany the north-American troops expelling al-Qaeda members from the Afghan mountains. Always accompanied by the chronicle, the objectivity matter imposes, where the author and the news’ object don’t distance from the other. The journalist even assumed: “I myself don’t believe in objectivity – no New Journalist does”.

John Sack went further by statig that any efforts to try to reach objectivity only distort the truth of the reports. But these statements weren’t the only controversy in Sack’s career. Author of many works, the book An Eye for an Eye: The Untold Story of Jewish Revenge Against the Germans in 1945 strongly shaken the public opinion, by approaching the sensitive mater of the persecutions between the Germans and the Jews during World War II.

Ryszard Kapuściński

Ryszard Kapuściński was another forerunner in literary journalism. Despite having collaborated with several communication organs, Kapuściński distinguished as a correspondente of the Polish news agency Polska Agencja Prasowa (PAP).

For 10 years, Kapuściński covered 50 countries for PAP. He lived 27 revolutions and coups, was arrested about 40 times and survived four death sentences. His most known works are the report of the end of the European colonial empires in Africa. His experiences during the war for Angola’s independence, in the 60’s and the 70’s, where gathered in the book Mais um dia de Vida – Angola 1975. Kapuściński published dozen os books, from reports and fiction to photography.

His style, unanimously called of “magical journalism”, would make of the Polish journalist one of the most acclaimed in the 20th Century.

THE PREDECESSOR

Nowadays, the chronicle genre is more established and it is greatly known. However, there are other older narratives that involved their readers in the stories and that equally resulted in books. In the 19th Century, Flora Tristándistinguished with her chronicles.

This side of her would make a big predecessor in Women’s and working class rights. Her work Promenades in London (1840) reports the impacting conditions the working English people.

However, it was with the book Peregrinations of a Pariah (1838) that Flora Tristán would reveal her gifts as chronicler. In it, the journalist reports the political events in a Peru plagued by civil wars, through a markedly ironical and critical style, where there isn’t lacking a sharp sense of observation. Unfortunately, the first copies of this brilliant travel report were publicly burnt at Plaza de Armas de Arequipa, in Peru.

In Brazil, in 1896, Machado de Assis would become famous with this chronicle titled «Canção de piratas», published in the column A Semana of the Gazeta de Notíciasnewspaper. This was one of many chronicles that Machado de Assis wrote to show his placement regarding delicate matters of the Brazilian political life, during the War of Canudos. This episode opposed Antônio Conselheiro (founder of a popular movement that tried to establish a socialist society) on one side, and the Brazilian army on another.

The Brazilian press of the time was marked by a mostly sensationalist tone. According to Machado de Assis, the press, by criticizing and calling Antônio Conselheiro a «fanatic», harmed the public opinion’s comprehension of the political scene.

Tired of the dubious quality of the press’s editorial line, Machado de Assis resorted to the chronicle to defend Antônio Conselheiro.

RUBEM BRAGA

Years later, also in Brazil, Rubem Braga would stand out as one of the biggest Brazilian chroniclers of all times. His journalistic career began during the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932, by writing to the newspaper of Belo Horizonte, the Diário Associados.

The chronicle became his specialty, and his pretty caustic and critical style, especially of the Brazilian Estado Novo, earned him several detentions. Braga would make innumerous contributions for several newspapers during his career, also acting as correspondent for the F.E.B. (Força Expedicionária Brasileira) during the World War II, for the newspaper Diário Carioca.

JOHN REED

In the other American continent, one of the big war chroniclers that went down to History was is John Reed.

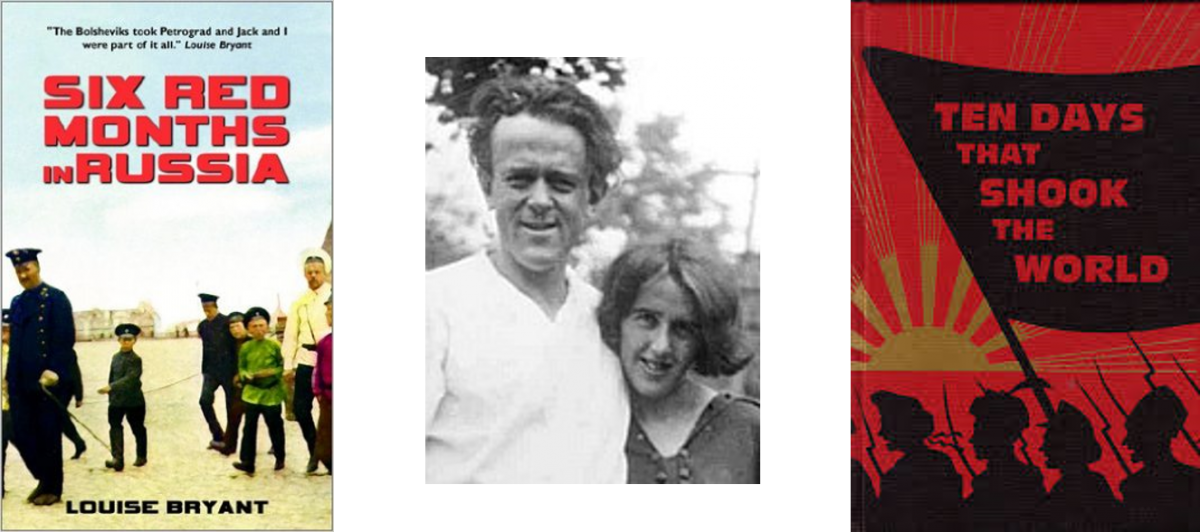

According to the presupposition that behind a great man there is always a great woman, Louise Bryant had her share as war correspondent. The two lovers, already husband and wife, became the first foreign witnesses of the Russian revolution, between august of 1917 and February of 1918.

From their hotel room, both reporters the revolution’s events in several articles, which were later compiled in the book Six Red Months in Russia (by Bryant) and Ten Days that Shook the World (by Reed). Louise Bryant interviewed several prominent feminine figures of the Russian revolution, such as Katherine Breshkovsky, Maria Spiridonova e Aleksandra Kollontai, works that earned her the titles of suffragist and feminist.

However, the passage of John Reed by Russia wouldn’t just be immortalized in journalism. The movie Reds, 1981, reports the story of the American couple during the October revolution. With the actors Diane Keaton, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson, the cinematographic work earned three academy Oscars, including the ones for Best Supporting Actress and Best Director.

Nevertheless, the Russian revolution wasn’t the first conflict that catapulted Reed’s journalistic career. Always a big defender of libertarian ideas, Reed saw the Mexican revolution of 1912 as a media event, that he reported risking his life. During this conflict, Reed even made a historical interview to Pancho Villa, one of the leaders of the peasant revolution, of whom he became friends with.

With the reduced scale of war events in the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, it wasn’t seen the need to proliferate the chronicle style. World War I would be the first big world scale conflict. All elements were gathered to invert that tendency in journalism.

THE WAR FACTOR

José Augusto Correia, a correspondente ofDiário de Notícias, was in Paris when it was commanded the population’s general mobilization to the war that was coming.

«Almost by enchantment, Paris’ civic aspect completely changed (…) the crowd took over the streets, parading on huge and compact columns», he would wrote in his «Crónicas de Guerra».

Other Portuguese that risked his life in the trenches was António Lobo de Almada Negreiros, the father of the artist Almada Negreiros. The correspondent sent his war chronicles from France to the newspaper O Século.

Despite of remaining in this publication until 1933, Negreiros wrote for many other Lisbon and foreign newspapers. In 1917, his experiences in World War I, reported in his chronicles, where compiled in his book Portugal na Grande Guerra.

«The battlefield is a big cemetery. The piles of the soldiers’ corpses are easily hidden to the sunlight that rotten them».

«The sound of the bombs, the cannons’ boom, the sounds of the signing rockets would give an idea of the monumental fireworks, if all these death instruments didn’t roar, as untamable beasts, for our tortured ears. We are climbing over the trenches, I don’t know what for».

ANDRÉ BRUN

At 36 years old, André Brun, the sent captain of the Corpo Expedicionário Português and with a career known in the Lisbon theaters as play writer, arrives in Flanders in broad war scenario. It would be these experiences that would shape his chronicles book A Malta das Trincheiras. In this ironic style, Brun reports in the first person how it was the daily life of the soldiers in the trenches.

«I, who had wrote for an album half a dozen of lines, which could seem of an easy humourism, saw how the multiple anguishes of my spirit, accumulated in the first eight months of trenches, took me to be a prophet in foreign lands». Expressions like «ir aos arames», «balázio» or «camone», used in these chronicles, also show that much of the slang that is still used nowadays was born in the Flanders trenches.

JÚLIO MESQUITA

Júlio Mesquita was a Brazilian journalists who followed the World War I developments through several chronicles of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo, of which he was also the first director.

In a weekly, journalistic and reflexive, analysis, Mesquista assumed the role of informing and explaining the events to readers. Despite the fact the journalist wasn’t in the conflict’s ground, it was precisely this distance that allowed him to report the war with accuracy and objectivity. The journalistic texts would end up being compiled in the work A Guerra 1914-1918.

Being the first conflict that would bring an enormous affluence of correspondents from several parts of the world, censorship was pretty tight and the journalists’ access to the frontlines forbidden

BASIL CLARKE

Basil Clarke was one of the correspondents that challenged this interdiction of Lord Kitchener. Risking jail, Clarke remained in Dunkirk, pretending to be a refugee, to access the stories coming from the battlefronts. Despite the difficulties, this illegal act quickly delivered results: Clarke was the first journalist to arrive in Ypres after its destruction by the Germans in November of 1914.

“The city, so silent and empty and waste, might have been unpeopled by a plague, shattered by a mad god. You looked, and still looking, could hardly believe”.

Besides, he was known for his memorale description of the atmosphere in Dunkirk after the Allies wond the strategic advantage in the battle of Yser.

His report of the bloody combat on Christmas Day of 1914 also offered a completely different perspective of the stories that went on about a Truce in Christmas. Clarke’s descriptions, embellished by a literary stile that challenged the objectivity adopted by western journalism, were an essential contribution for an independent war report.

In January of 1915, Clarke was forced to leave to England, under the threat of being arrested by the police. The adventure of his life was ended. Later, Clarke stepped aside from journalism and became a Public Relations pioneer in the United Kingdom.

PHILIP GIBBS

Philip Gibbs was another journalist that suffered in his skin the censorship imposed by the militar during the First World War. He escaped several times from the British and French authorities in order to be able to take his battlefront stories to the Daily Chronicle newspaper, but he was also arrested more than once for his persistence.

His war reporters were considered by many as prodigious. Besides the countless chronicles he wrote for the press, Gibbs’ work about the conflict was noted through the books The Soul of the War (1915), The Battle of the Somme (1917), Now It Can Be Told (1920) and The Realities of War (1920).

“Pains and penalties were threatened against any newspaper which should dare to publish a word of military information beyond the official communiques issued in order to hide the truth”, Gibbs wrote later about his experiences.

Gibbs was captured in Le Havre, in 1915. After being threatened with “painful consequences”, the journalist decided to return to England and retire from war.

His work as journalist continued – and he became to be war correspondent again when tensions reignited in Europe in 1939, even if just for a while. It is not possible to speak about chronicles of the First World War without mentioning Ernst Hemingway. The experience of the then journalist driving ambulances in the battlefront, in Milan, would serve as inspiration for his non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon.

MARTHA GELBORN

However, it was in the Spanish Civil War, in 1037, that Hemingway, a North American Newspaper Alliancecorrespondent, wrote about the armed conflicts. His experiences resulted, later, in his acclaimed novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. It equally by that time that he met Martha Gellhorn, another war correspondent sent by the Collier’s Weekly to cover the war in Spain.

Gellhorn’s journalistic career was characterized by the coverage of the major war events of the 20th Century. The World War II became the focus of her most known chronicles.

Gellhorn reported the war from Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore and England. Later, the journalist admitted: “I followed the war wherever I could reach it”.

Due to lacking press credentials to assist the Normandy disembarks, Gelhorn hid in a toilet of a hospital-ship. She was the only woman president in the D-Day, on June 6th of 1044. She was equally among the first journalists to cover the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. In 1999, it was established the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. Among other distinctions, Martha Gellhorn was the only woman to be recognized in the American Journalists stamp collection of 2008.

AT LAST, THE CHRONICLE

When the press was giving its first steps, the line between the writer and the journalist was very fine. The chronicle is the genesis of this crossing between journalism and literature, when it wasn’t known when the story started and where the facts ended.

The chronicle’s characteristics soon kept the readers’ attention. The formal approximation to the news’ realism, the first-person narrative and the up-to-datedness of the events described, surpassed the simple empty interpretation report so connected to the journalistic coverage.

More than informing, the chronicle allows its author of assuming a more personal and reflexive placement. From journalist to writer, the author becomes one single figure, with the endless power or transporting his readers to other realities, unknown until then. The path to cement a place of its own for the chronicle was taken.